Ian Ortega, the Managing Partner at Ortega Group links up with Arinaitwe Rugyendo, the man that founded Red Pepper Newspaper in his 20s and brought to life, what Joseph Schumpeter calls creative destruction in the media industry:

Ian: As we start off, I just wanted to know about failure. Of late, you’ve had what I would define as a trying moment. What keeps you going? Whereby you take these big risks and then you keep going.

Rugyendo: What keeps me going is that I am a very optimistic person. I am not a pessimist. I have that premonition that something can come out of pain at the end of the day. Something positive can come out of pain. So I always think something positive is going to knock at the door at the end of the day if I keep in there and try to do the right thing out of a bad situation. This has been my case for a very very long time.

Looking at my own circumstances. It is a challenge that I have always faced.

Ian: So you didn’t have a smooth childhood background? Silver Spoon?

Rugyendo: No! Never!

Ian: What is that memory of your life where you think hardship formed you?

Rugyendo: I grew up without a father. My father died when I was 3 months old. By the time I was getting to understand what was all around me, I found myself with a mother in the staff quarters of a primary school. That is where we were. That was our home. That was our land. That was our garden. It was our kitchen. It was our place of abode. My mother was a primary school teacher. That is where we were, no hope, nothing! Depending on just her salary and that was it.

Along the way there were several incidents that happened around 1983. The first incident was the burning of houses belonging to Rwandese in that area of Ntungamo where we were living. And we had a lot of friends, some of them relatives. The pain of just seeing people move and then for us we got hold up in a church and we could not go anywhere. And then later in 1986, we had to be forced to move from where we were because my step dad at the time had become a Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC) winger. My mother was NRA. So there was that constant problem at home. And I was just getting to grow up. I was about 8 to 9 years old at the time. So we moved to Rwampara in Mbarara, again, to another primary school. And that is where we were dumped. And my Stepfather left us. He just left. He moved and disappeared. He left us their because my mother was still a primary school teacher.

Ian: Your Step Father had no children with your mother?

Rugyendo: They were there. I have my siblings. One died of course. So they were there. I was the first born. I was in P.4 at that time in 1996. So we were living on handouts. People who were neighbouring the school were the ones who were giving us ‘matooke’ plus posho. So at the age of 8 I was mature. So you could see such a situation where you drink your breakfast, you drink your lunch, it’s porridge and supper is when you hope for some food, some kind of hard food. Sometimes it doesn’t come. Sometimes it comes. And that was it. But we stuck there. The church helping. The catholic church in the area was very instrumental. By the time I was completing P.7, my heart was telling me to join the seminary. Go for priesthood and disappear there.

So I worked hard and passed and went into the Seminary for my Senior One. I went to Kitabi Seminary in Bushenyi district. It is one of the top schools. I usually see it on the lists. So I went there. At that point I really took over the home. I became the father in the home. I was doing all sorts of work. On people’s plantations. I would go there and dig, get some food to eat. Sometimes those who had big land would give you where to grow your own food. I would do all that during Holidays then go back to school.

Fast forward to the time when I completed S.6, I couldn’t proceed with Priesthood. I told my mother it is not going to be easy for us if I proceeded. I would rather not go so that I stay, take a shorter route, come back and rescue you guys because these conditions are not very easy for us. So I went to Makerere University.

While at Makerere I did two jobs. One, I was digging in Professor Oswald Ndoleririe’s farm which is found in Kiwawu, Mityana district.

Ian: So when would you go to the farm? On the weekends?

Rugyendo: No, I would go only during the holidays, during the long vacations. I went twice, in the vacation of end of First Year and also end of second year. And towards the end of my second year, I channeled myself towards waiting tables. I went to work at a hotel, Calendar Rest House in Makindye at the time. Now it is called Calendar hotel. That was around 1998.

Ian: How much were you earning as a waiter?

Rugyendo: UGX 50, 000! And I would send about 80 percent of it back home for my siblings to go to school, as pocket money and stuff like that. It was a lot of money that time. In 1998, UGX 50,000 could be an equivalent of 150,000 now. During that time, I managed to start training myself in writing.

Ian: You had pursued what course at campus?

Rugyendo: I did Political Science and Sociology. I missed Mass Communication by a whisker. At that time I could not manage private sponsorship. So I went for what Government gave me. And that was Political Science and Sociology.

But I told myself I must write. At that time I started writing a few stories. I would walk from Makerere on foot up to the Monitor in Namuwongo. Those were the days when I met your father and Charles Obbo. Those two guys and they kept encouraging me. They told me, keep writing. And that time I was lucky. That was the time when Besiege had caused problems with his letter. So I did one of the big stories which I still remember. It was the cover story. And I had walked on foot with it.

I met Brigadier Kyaligonza at a certain Bunyoro students’ party at the Faculty of Agriculture. So I asked him what he thought of this Besigye letter and what Besigye had said. So he replied; “what Besiege said is fine and etcetera.”

Ian: Did he know he was speaking to a journalist?

Rugyendo: Yes, he knew. I told him I am from the Monitor. At that time I was only just a freelance. Luckily there was also a Radio Uganda chap who had a huge radio recorder. So when we talked to him he said; “No, these things Besigye is saying are okay. Only that he is using a wrong platform. But he is raising very good points.” So I scribbled something. There were no computers at that time. I scribbled something by hand on a piece of paper.

The next day I just walked to the Monitor. I told people in the newsroom; “you guys, I think I have a story here.” So guys were wondering; “did you really interview this man?” I said; “yes, I interviewed him, there was even a Radio Uganda journalist. You can listen to it maybe this evening or during News Hour.” And I think Charles and Wafula confirmed. Because the next day I was the headline. That was the best day of my life. The story was titled; “Brigadier Kyaligonza backs Colonel Besigye.” At that time, how a serving general, moreover a retired bush war fighter hero backing colonel Besigye was something very huge. It was a big story. The whole country was spinning that day.

So finally I graduated on 17th March 2000. The same day we graduated was the same day Kibwetere burnt people in Kanungu. So these people at Monitor looked around for Banyankore who were familiar with that place and here I was. Did I even have my graduation party? No. Next day I was on a bus to Kanungu. I stayed in Kanungu for like a whole month. And when I was there, my little French I had studied at Kitabi seminary helped me to turn myself into a translator for international media that were coming from RFI, others from Belgium and all these places. I would talk to the locals and translate for them. Everyday I was getting about $100 dollars. It is the money I used to build a house for my mother.

Because my mother had managed to buy a small piece of land but she was in a grass thatched house. So I managed to rebuild it, put iron sheets and here I was very perfect in 2000.

Ian: When you look back in hindsight, are you thankful for that struggle?

Rugyendo: I can say Yes and No. Yes because it hardened me not to take anything for granted. But also humbled me as well. You get humbled at a very young age to understand that what you don’t have doesn’t excite you, and it doesn’t bother you. You feel contented at a very young age. And that was it. You know, this is our situation, you can only use it to better yourself and struggle hard. So there was really that impetus to find so hard and get out of that situation.

In a way it has now created a negative effect. Which is the urge to prove a point all the time. The urge to prove a point all the time that you know, I was deprived so let me prove that I can do something, very big things. So along the way you find yourself even making mistakes. Like waking up one day in 2001 and resigning a job at Monitor. My mother cried. I said I must resign it. Where are you going? I said I am going to start a newspaper. And I didn’t have money. Just with my colleagues we said we are going to start. And we pooled some money. I was only earning about UGX 240,000 from Monitor at that time. So we pooled, the others were at New Vision, we pooled and we had UGX 700,000. We just came here in town using diskettes and started.

When we started with borrowed computers, one was a laptop and another a PC. We started from somewhere in Kavule. One of us knew one of the printers in industrial area, we went and printed on credit. We put the papers ourselves on the streets, sold and the paper started off like that.

Ian: That is unbelievable. It is something I am trying to deconstruct how you don’t fear to venture out. I would expect that if you’ve come from this abject poverty, now you are here in this moment, you have some fair amount of comfort, you’d be more scared to venture out.

Rugyendo: No, that’s the problem with deprivation at a very very young age. You always feel a sense of insecurity. And thinking that what if something goes wrong. What if this one basket of eggs that I am carrying collapses? You need to keep moving. And because of that deprivation, there’s not so many people around to help. So you feel you don’t give a damn. So you go in and dare. Because if you don’t dare, no one will dare for you. So you keep daring, throwing in a few things here and there knowing that something perhaps can jump out and you become better than what you are.

There’s also the urge to improve the situation you are in and the situation around you keeps you thinking that you must take risks. If you don’t take risks, no one will take them for you. But also huge risks tend to come with big dividends at the end of the day. If you look at many people who have made some strange contributions are people with the kind of background I have. They came from nowhere and they just have to struggle to better themselves. You’ve seen them around the continent.

Ian: Because I was speaking to Amos Wekesa and he told me his greatest motivation which he also thinks should be everyone’s greatest motivation is that he tasted abject poverty and he just never wants to go back there.

Rugyendo: You can see. I have not talked to him but the thinking is the same. You just don’t want to go back there. Recently before my mother died I was building a storeyed house for her in the village. And people were asking me why are you doing this? I said I am making my statement. Because there was a time when we had no roof. No roof, no land, no food. So I feel that sense of deprivation has to stop somewhere. I say let me build this huge house here, let her go in and enjoy.

Ian: So she died before she moved in? Didn’t that crush you?

Rugyendo: Yes she died just before she could move in. It crushed me. That is the pain I still suffer even up to now. Because she died suddenly. In February she had been feeling pain and we didn’t know it was cancer. She died in February last year (2017) on Heroes day. That moment was really tough for me.

Ian: Let’s go back to this point. You begin Red Pepper at 23, when does it take off? When does it break even?

Rugyendo: We had this one room where we were staying in Makerere Kavule. I can take you there or direct you there. The building from where we were renting is still there. We were renting at UGX 250,000 a month. But we were making a hell lot of noise from there. People thought we were huge yet we were very ‘hopeless.’ I think what took us so fast was the brand that we undertook to publish. Because we said we cannot do what Monitor is doing, we cannot do what New Vision is doing. So we went to work and we noticed that we could do a tabloid here. Tabloids were already successful in the United Kingdom. So why not here? This is the first of its kind and if you do something unique, you might create a readership of your own and that’s what we did.

Ian: How did you come up with the name?

Rugyendo: One day we were eating pork trying to start, that was one evening in Wandegeya. So we had initially come up with a name called Digest aka The Digest. We wanted to do analysis. We digest the news for people and explain it to them. So we were eating pork. So one of our colleagues, one of the other directors named James said; “By the way, why don’t we call it Red Pepper?” Because we were using red pepper to eat the pork. We asked why. Then he said; “you see red pepper if we didn’t have it, we would not digest this pork. And red pepper anatomically, it sounds like a paper that has been read or the paper which is the only read paper. So it is like you you I want the paper. So the vendor will say; “you mean read paper?” Because when you say I want the paper, you mean read paper.” We thought it was a real marketing coup against the other newspapers. That is how the name came.

And what does red pepper do to the body? It is nutritious. It is sour in the mouth but finally it helps with the digestion and nutrition. It is medicine at the end of the day. So why not news or stories of that nature? Bitter truths but at the end of the day it becomes a social medicine. That is how red pepper started. And I think there was no other paper named like that anywhere in the world.

Ian: Didn’t you feel scared taking on the tabloid form because I guess at that point in time Uganda was very conservative? I remember there was that magazine that had a cover story on a Makerere student in a bikini wear. I think Spice by Edmund Kizito.

Rugyendo: It was actually called Chic Magazine.

Ian: I was reading of how when her story came out and the whole country became hell for her.

Rugyendo: It was not even a bikini. It was just something skimpy. And everybody was like this cannot happen. She even had to go and get saved. But her picture looking back was too normal. But that time Red Pepper had not started.

Ian: So when you people start, didn’t it bother you that you were going to be contrarian?

Rugyendo: Why we were not scared a lot was because we were young. You know when you are young, there’s that rebellious part of you that doesn’t give a damn actually. We were not married. We were just there, boys wondering about. Who cared? We didn’t have cars. Go in a bar and drink a beer and not care where you have slept, in the morning you’re back on the desk. We were not bothered at all. And we really came to have a problem with the Pentecostal movement. They took us on directly. They wanted the newspaper banned.

But there was another divide that said, look this guys are saying the truth. So the debate was too much. Why we were not scared also was because the debate worked for us. No newspaper would not wish to have that kind of publicity where even CNN came here, BBC was allover the place looking for us, wondering what kind of paper this was. What kind of people are behind it? And every time they made noise, the media houses were catching the story, allover addressing press conferences and appearing at talk shows, WBS at that time. Radio One. There’s a time we had a real fight in the studio with Pastor Ssempa in the Radio One studio and the show had to be stopped. The next morning everybody was talking Red Pepper. Even people in Karamoja were wondering what is that paper? Even people who didn’t want to know about it were forced to look at it. Even those scared to read it in public would hide it under New Vision and read it. That is how we broke even.

We actually encouraged these people to keep arresting us.

Ian: What year did you break even?

Rugyendo: That was 2003. One and a half years after inception. It was so fast because of that controversy. There was one of those stories that caused a lot of controversy. It was a serious human interest story. Photographers went to the pitch and captured students having sex in the open. So we took the pictures on the front page. The whole Uganda was like; “what is this???” But our editorial was very clear. We were condemning this act. We said; “you parents you didn’t know, you’ve given up on your responsibilities, here is what is happening and here’s where it happened.”

When the Police was arresting us, some sections supported us saying; “look they have helped us we didn’t know. “ So the police went and asked the beach management around the lake to increase lighting. So we had a lot of moral argument. They could not win. They took us to court and the case collapsed. The state lost interest because midway during the trial, they could not sustain it. Because they could not justify. The story was clear. This is what happened. Was it news? Yes. And did it corrupt public morals? We said No. Bring us evidence of who is corrupted. And they could not produce a single witness. The case collapsed and was dismissed.

But during that time of like 3 months of the trial and the hearing. You would jump out of the court, CNN is waiting, you jump out of this, BBC Focus on Africa is waiting. They gave us a lot of publicity. Suddenly we were this strange newspaper out of Uganda and has not been seen anywhere on the continent. And our numbers were peaking. We hit about 25,000 copies and at the point we were able to buy the Monitor machine. Monitor was trying to sell its old printer and that’s how we bought it.

Wafula called me and said; “Rugyendo, look we don’t want this machine to get out of Uganda. We need it to stay around. Because Monitor may not print with New Vision if it gets problems. We want people whom we can deal with and we can see you guys are making some money.” So he said; “how much money are you making?” I said so much, so much. So he asked that we commit 5 million shillings to us and when you reach 50 percent we give you the machine. That’s how we bought it with no loan. We kept paying a weekly cheque. We went without salary for two years in order to buy that machine from the Monitor. We invested 5 million shillings every week. And they gave us the machine when we hit 50 percent. That is how we brought it here in this building here. There was no fence it was a bush. We only managed to put up that factory where it is that is how we brought the machine. The day we brought the machine in 2005 is also the same day we became a daily.

Ian: Hasn’t this journey earned you lots of enemies?

Rugyendo: Yes.

Ian: Because one of the things that happened when you guys were in prison. Some divides were celebrating saying; “finally.” There was this huge division once again, the side that sided with the devil and the side that thought the devil deserved it.

Rugyendo: I think it has earned us frenemies. Because throughout this period when I heard about all these comments, they were mainly related to two things. First, these kind of stories are not anywhere so they are bound to be very bitter. When you for example write that someone has divorced his wife because she was sleeping with someone else. This is a story that is definitely going to anger someone. It is true we are informing the public but the couple somewhere has had problems with the story. So we have a huge section of those kinds of people. Correct stories but they are social and personal. Because tabloids are really social and personal. The other mainstream journalism focuses on policy. A borehole has been launched here, road commissioned here. How does it affect an individual? The tabloid speaks to the individual. What is the personalisation of that road? So the tabloid will go for the corruption on that road, will go for that person who has stolen cement on that road. So those kinds of people once they are arrested and taken to prison, they are going to be very bitter.

Then two, along the way some stories we got them wrong. And when you have such a personal story and then you get it wrong, someone will be bitter.

The third one, there was this accusation of extortion on the part of our journalists. What we discovered is that whereas in some cases some of our journalists were culpable. Those we would expose openly in the paper and alert the public not to deal with these guys. There is also a group in town that took advantage of this kind of newspaper and its investigative lethal style to now impersonate Red Pepper. There is a cartel of people in this town, very well established, connected even with security agencies, with investigative agencies. Because Red Pepper is very bold. If I come to you and say ; “Ian here is your picture of you sleeping with so and so, it is coming out in Red Pepper , you are a Managing Director of a Bank, what are you going to do?” Your natural instinct will say I will plead with this person and then he says let’s talk. And most people have been extorted like that.

Guys go in town and properly investigate and most of the stories are very correct. So this cartel will say; “you need to give me 50 million shillings because UGX 10 million is for Rugyendo, UGX 15 million is for Richard, UGX 5 million is for Ben Byarabaha, 10 is for Johnson and 6 is for James. And then for me I can only take 2. If you don’t, tomorrow they are coming. And you know them.” And these are cases where we are not anywhere involved. And then these victims because they are very scared, they have been caught red-handed. They have nothing to do. So somebody ends up selling up his property or gets a loan and pays the money thinking it has gone to Red Pepper. And the guys keep it like that. So we did not know these people until this incident. I am telling you the truth. And this is the very reason we have an advert running everyday to warn people not to fall victim. We are alerting the public, should they sense anybody trying to come and claim that they are working for Red Pepper, then let them kindly alert us. But people don’t even tell us because they feel they might be ashamed. They just decide to keep quiet. So such a person will always remain bitter. I can assure you there is no policy here, there is no director here who has ever done that. None, not even our senior editors. Those we’ve caught doing that, we’ve punished them and actually sent them away.

Ian: So if you were to start all over again, if you knew what you know now, is there something you would have done differently? Would you have been a bit more forgiving on some stories. I am trying to say this because when the first sex tape came out from UCU and we had it on www.bigeye.ug and then it was such a big thing. On hindsight I realise maybe this is a whole lifetime of a person that gets crushed by such a story.

Rugyendo: In most cases you feel that. You understand that journalism is a cause. And why it is a cause is because there is context. You realize that society like ours where jobs are scarce, where levels of influence are limited, levels of opportunity are also very limited, you realize that may be certain stories maybe are better not run. That is on way to think about it. Especially for stories that are not entirely criminal, those bordering on personal mistakes. Those stories could be told in a certain way. That feeling keeps coming once in a while especially as we grow. Sometimes we did those stories when we were cheeky but now we realize may be we could have exercised more restraint for something like that because of the context. In more open societies, this is fine. People will not mind. But in closed, conservative societies, the nature that is ours here, maybe sometimes context needs to inform the kind of decision you need to take when confronted with those kind of stories.

Ian: What is the one thing you regret and why?

Rugyendo: My generosity. Because of my life history, I am extremely generous to the point of even depriving my own people certain things because I can’t stand seeing people in pain of deprivation. So I go on picking people. And I pick this trait from my mother. Pick people, give them school fees, they misuse it, don’t come back. I regret this generosity at a certain point because you don’t see any returns back and when you are in trouble, no one comes to you. That’s the extent in which I regret that. Because the extent to which you go an extra mile to be generous is not the same extent people are generous to you. When you are in trouble, people don’t come. Then you realise people are actually mean. You realise maybe I shouldn’t have wasted my time.

The other one is trust. I over-trust people. And I have lost lots of chances, I have made lots of mistakes because I have trusted people especially in business. You trust a partner, you entrust them with finances, with running the show and then you realise at the end of the day you can’t deliver the contract. And there’s one particular chap that really made my life to be hell.

I tried to venture at one point in 2011 into road construction. Because I was not a technical person. At that time I went for a leadership course for some months. When I came back, I realised that the guy I was partnering with had messed up the entire contract. And we had been pre-qualified at UNRA for the next 3 to 4 years. Brazenly and stupidly the guy messes up the contract and we cannot work with them anymore. You trust somebody who doesn’t have the kind of vision that you have. So he messes it up, money that was already invested, all gone, a road poorly done. I had to beg people with machines to help me finish that road. It was a murram road somewhere in Kitgum. Luckily enough we finished it and got a certificate, the money that came out of it, all of it went to pay money lenders. That is one of the worst incidents but there are several hundreds of them. I regret it. It is as if it is a divine thing, as if in-born to give, and then to trust. Either I don’t know whether it is a biological weakness. But if it is, it is something I regret.

Ian: Going forward, how do you deal with these cases of failed judgment? Do you have like mental models? I will give one of my models. I realise when people fail, they tend to blame other people, when they succeed, it’s more about them. And the other is that when people over-promise, they tend to deliver less. Do you have those mental models that you bring in to try and guide your judgement?

Rugyendo: Yes, I try to exercise a lot of patience with people who even openly make mistakes. I tend to feel we don’t have the same level of appreciation of certain things. I believe in improving. So I am very patient and tolerant. I exercise a lot of tolerance, restraint because with those you have a lot of time to think through a decision. So I use much of those, restraint, patience, tolerance and then at some point you realise maybe you should have taken a decision at a certain point and didn’t and therefore this or that happened.

I also tend to retreat to myself. I end up like being a loner and then try to think through about what I could have done wrong. How do I avoid it next time? And then bang, a solution comes and then I go. I tend to do a deep deep self-reflection. I try to think through my mistake and then find a solution for my own. I tend to be introverted a lot.

Ian: Is self-reflection something you picked off from the seminary? You know those siestas?

Rugyendo: Seminary enhanced it. I think, I picked it from my mother. My mother is the one who would be feeling a lot of pain but you would not know. She would be angry but you would not know. So I feel it’s a biological thing and I have picked it from her. The seminary only enhanced it because it gives that kind of environment where you retreat to yourself. We call it meditation in the seminary.

Ian: What advice would you give to a smart, young, very driven University student just starting out? What advice do you think they should take and what advice should they ignore?

Rugyendo: That age (20 to 21), the head is working like a printing machine. There are so many ideas that are coming into your head. And that is the right age where you think more genuinely. And whatever you think, is something that is going to be your dream for almost like the rest of your life. If a young person at this age believes that this thing works, they must go for it. They must use all means possible to pursue it, even if they make mistakes. Because that’s the chance a young person has, you don’t have any other chance. That chance of the age between 19, 20 to 25. It is a time of disruptions. It is a time of making so many mistakes. The minds are thinking, the minds are innovating, the minds are creative, that is when they are at their best. They are thinking, restless. For me one should be able to pursue something that has comfortably appealed to all their five senses. This is what actually happened to me at that time. I was not fearing anything, whether they saw me digging anywhere or working as a waiter, I said No, I must pursue this because I believe it is something that is going to work.

What they shouldn’t do or advice they should ignore is when somebody tends to discourage you. I didn’t listen to anyone, not even to my mother who tried to stop me at that time when we were beginning Red Pepper. She would not understand why I was resigning a job where I had been appointed a Bureau Chief that time of the Monitor in Mbarara. Bureau Chief is such a big thing, why are you resigning? I said I feel this thing is going to work and if it doesn’t work, I will not come back. And I asked her, do not follow me. So it’s like you go into a wall and face it. My mother discouraged me, another person also discouraged me and I said; “Oh, Why? I have the energy. Why? I refused to listen.”

If somebody says don’t go there, you will have a job in ministry of Public Service, go for it as long as you believe it is going to work. It’s only you who knows if something is going to work by the way. At that age you can easily tell. You feel it, it is in your hands. It is in your veins. You feel restless. This is actually what happens to you. You feel a lot of restlessness in you, you can’t sleep. You keep waking up and writing something down and then going back to sleep. You wake up again, scribble something. You are talking about it a lot. Whoever you meet, you are talking about it with them. Then you are scratching your head all the time. Again, you are restless. In your mind you actually envision it, you start seeing it. You close your eyes and you see it. Now that is the right time.

Ian: I see it with Indians who are very more of intuitive. And I would really agree there are those moments when you know this is it. You can’t even listen to another party. Could that point to maybe something beyond us, this still inner voice?

Rugyendo: I can give you examples. If you look at these guys in Power, that time, explain to me how somebody dares an entire fully armed barracks with only 27 guns? And he has no car. You just grab someone’s car, uses it, abandons it on the road then you just head into a Barracks. Isn’t that madness? I don’t know how you can call it. It is recklessness of the highest order. It is madness. But look at the age, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, that was the age. There’s a lot of things going into your head to the point of running mad. Something might be talking to you. But let me say that is the time when you form your vision. Something either divine is telling you to take a direction at that point.

If you look at people who have not made use of that moment, they have tended to be conformists, they are the ones led, they are not leaders, they can’t take decisions, they believe in a straight way of doing things. And perhaps things are done for them. That is the kind of later state they believe in, in their later life. You see it. And they start making mistakes at the age of forty which they call midlife crisis. They start wishing, I wish I had done that thing I was thinking about. Let me tell you Red Pepper has succeeded for 17 years because we thought and did it at that age. If we had missed that critical moment, children would have started coming in, you are 30 years old, you are thinking of your Masters Degree, children are going to school, you now can’t be a dare devil when you have something to lose. At the age of twenties, you have nothing to lose, except maybe your parents. What do you have at the age of twenty? Nothing. So it is a time when your biggest asset is your head.

Ian: But how would kids be able to jump out of the trap? Because there’s the way the narrative has been setup. There’s a way the system has been setup of how things should be, the way society has set it up. What is success to most Ugandan parents? You working a corporate job, earning a salary, and being there. How does a person transcend that fear of other people’s opinions, that fear of disappointing many? And that fear of saying all my friends and peers are going to be doing this, but I am going to take that other path? And be wrong for maybe the next 5 years, 10 years and win?

Rugyendo: Exactly. We were wrong for 5 years until people started seeing us driving cars. And they realised, these guys are making money. That was around like 2005. Then people started realising that maybe we were not wrong.

The transcending of this fear comes down to character and the environment that shaped you, the role models you look up to.

Ian: Especially in cases where people have not grown up with those examples? Your father has been working a job, your mother works a job, your sister, your aunty.

Rugyendo: When it comes to our context, it is the background that is largely shaping that transition. Many people who have done this, have had precarious backgrounds. The ones who are born comfortable tend to think things are fine. The connections are there, why should I bother? There was a period in my view when that was the in-thing. People who had no relatives in government, who had no connections, had no background. There is that feeling that you need to prove a point against those that think you are not supposed to be thinking the way you are thinking. The urge to prove a point is what impels you at that point in time to say; No I will pursue this direction because I believe in it and I know it is going to work.

Partly it could be in-born. Some of those traits are in-born. Because you find these traits in certain segments of the kids who are born rich. You find they are very versatile. Their father has money but the kid wants to move on his own. And these children are here in town. I have seen them. Like the children of Wavamunno, the children of Aga Ssekalala of Ugachick, and also the children of these Indians. It is to do with character, environment, perhaps also natural instincts.

Ian: In your view, smart work or hard work?

Rugyendo: I have tasted both worlds. The world is very fast. But, you can work hard without being smart. Again, you can also work hard in a smart way. A bit of both is what I would go for.

Ian: When you think of success, what three names come to your mind and why those names? In my case I would think of a man like Naval Ravikant. Makes a lot of money then decides to go into angel investing and he doesn’t believe in having a typical day, setting up appointments two weeks in advance. And he’s had a whole view of it, family, meditative. What names do you think of?

Rugyendo: I want to start with one man and that is Yoweri Museveni. You look at his background, look at the time he was 12, 14, this is someone who says I am going to be president of this country. And he pursues it and he becomes president and stays there. There is something for me to pick there in terms of someone who believes in their vision and pursues it and doesn’t want to listen to anybody. And achieves it and actually does it, and disproves every little critic. That to me is success. That is one individual I want to keep studying a little bit, he’s a bit intriguing.

Leave alone the other issues that maybe surrounding him, and what people think about him. But the pursuit of that dream, the pursuit of a single minded dream. And if you want to prove my point, these days he says; “I have been on this thing for 58 years.” You see that kind of talker. So 58 from 73 years, it means he was around 15. And it is true and there’s a track record to that. You can easily find it. He pursues his dream consistently and gets there and does it. And all these people you meet them and they say; “but he used to say this and we would say No.” Now there he is and you can’t do anything. That to me is something called success.

The second one is a man called Obama. Obama is an exemplification of nothingness to something in a world that meditates against every little opening that you can pursue. But somehow, I don’t know whether it is by divine grace or anything, someone just breaks the barriers and is up there. Obama is one other case that I can comfortably quote.

This man, Mukwano. Comes all the way from India, thousands and thousands of miles away, lands at a coast and then walks inside barely with nobody and starts tilling your land. Then builds an empire. That consistency, that belief, that lack of fear of the unknown and you venture into the wilderness, in the furthest of lands, somewhere in the dark continent, different skill, different language, but you mingle and then people call you Mukwano and then you take over every homestead. Every homestead uses your product, that is success. And you started from nowhere, from nothing.

Ian: Which three of your possessions do you count as most valuable? And Why?

Rugyendo: One is my house, the one I live in. It is a house I built when Red Pepper had started making really good money in 2005. It is a storied house. It is the most valuable possession I have. It is actually the only one I have in Kampala. People think I have a lot of property in Kampala. I don’t believe in accumulation of too much wealth that you can’t even control and it leaves you sleepless. That one house that I have in Kampala is something I set out to do daringly because I didn’t know I could build a storied house. And that time I was only 28.

So people said; “but you man, this is for people who have retired.” And I said, I want to do this because there was a time when I slept in a house and whenever it rained we looked for a shelter within a shelter. So I want a complete opposite of what I went through or what I possessed at that point in time. And that one really came out of that anger to prove a point that now here I am.

The second one is humility. This virtue is in-born. I can’t just say that I am not an arrogant person. But out of 100 people I have met, 95 percent think I am very very humble, empathetic, name it. And this has won me more friends than enemies. Even during this crisis, that we just had, I got evidence, real concrete evidence of people talking well about me, and fighting hard to even get me out of jail as an individual because of that virtue. It is such a huge asset that even when we were out of this crisis and I was running up and down trying to make ends meet. Many people have come on their own to promise very many things. They say we know your company is down but we know you, we think here is an opportunity try it out, here’s a contract, try it out. Some of them I don’t even know who they are. You are there you find money coming anonymously on your phone from a source you don’t know. You call back and someone says; “no there’s a time I was this and this stuck and handicapped, you helped me but you don’t remember me.” If you can get a combination of generosity, humility, empathy, if you could brew these and get out one word, that is the asset that I really value. And it comes so naturally. And because of this, I believe it is a very special asset which I even feel and know it will take me somewhere. It will take me very many steps ahead.

Finally, it is my family. I have had almost a family-less family, having been born and you see no father. You don’t have a father figure in your life and then your mother is there struggling, living like a man at one point, then you are the man of the home, aged about 15, you know that kind of situation is not the best at all. So you look at other people, they have their fathers, they have their families, for you are there, you don’t know where to go. People are going for Holidays, for you, you can’t go anywhere. Then you got a home, but you can’t even call it a home because your mother is incapacitated. You wish maybe if I had a dad he would also work hard and may be we would have cement in our house like the rest of the other people. That kind of sense of being family-less is something that has been compensated by the very good family that I have now. I am blessed with four children, two girls, two boys and very interesting chaps, very mad, very intelligent, just there with debate in the home. One aged 10, then 9, then 6 and 3. So you realize that completeness is a very strong asset that when you stand up to say something, people entrust you with responsibilities.

I am Chairman of three boards now. Because of my character. My character has brought me very many connections and because of these connections, these boards think they can cash in on those connections. You see what Character brings you, it brings you wealth and connections at the end of the day, free of charge. And you become very likeable very easily. And because of a family, people tend to take you very seriously. You are no longer the other rowdy 23 year old who was starting Red Pepper. Now I am in my 41st year. It means quite a lot in terms of status and trust.

The other asset is my Late Father. He was born very poor. he struggled on his own but died before he could see me grow. He believed in a just and fair society. He cherished education as a liberation for the unfortunate. He was a Mandela. So what motivates me to take risks is because I want to live and achieve the dream of my father.

Ian: What’s a habit you’re trying to change right now?

Rugyendo: The habit I am trying to change is drinking. Because of those problems, I found myself drinking to try to chase stress away. And I realise it has not worked. For the past one year, after the death of my mother. I have been on and off trying to fight it. I can say I am almost like 70 percent off. It is one that tends to soil these good things I have been talking about. At one point you are there. Because I love music a lot. I am the type who gets drunk and I invade the Deejay’s box and takeover the deejaying myself. And by the time the music is done it is like 5am in the morning. You are just there, you don’t know what you were doing, just in a happy moment.

Then you remember you had a meeting to accomplish the next day and you have failed. That’s the only one. I had set a target that I would stop drinking at the age of 30 and I failed, then i pushed it to 35, failed. Now I am in my forties, I cannot go on anymore.

Ian: Do you often read? What are those books you’ve re-read?

Rugyendo: I have re-read Sowing the Mustard Seen like 3 times. It takes you into a life of somebody that you feel you are identifying with, a struggler, struggling against all odds and you feel there’s something worth reading about that book. I read it first at campus in Political Science class then later around 2005 then lately during this crisis when he gave us a new edition.

The other one I have re-read over again is a book by Dr. Ben Carson. It is titled; “Think Big.” It is one that inspired me the most to think big. That one I have read like four times.

I would add Africa: A Biography of a Continent by John Reader. It talks of all of Africa’s potential given in its proper historical context dating as far back as 100,000 years ago.

There’s another small book I have read all over again. It is Selected Articles on the National Resistance Army War.

Ian: Do you have a life philosophy? How would you break it down?

Rugyendo: It is be good to the people on your way up because you will meet them on your way down.

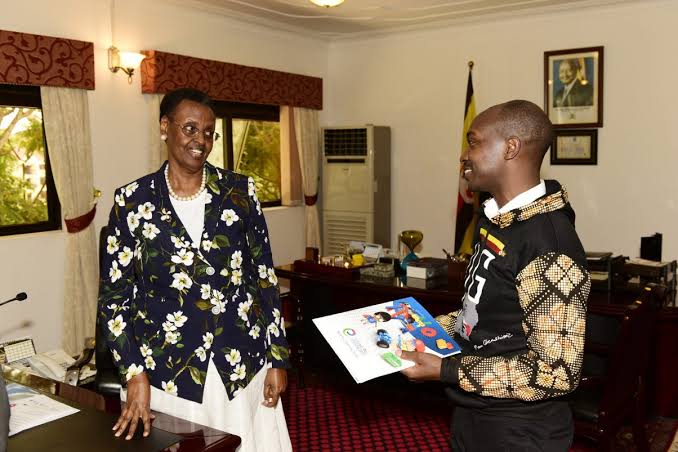

Ian: Speaking of the future, next 10, 50 years, what do you think are those things someone should look into? I know you are working on an exciting project of Young Engineers. What are those trends that are going to define the next decades?

Rugyendo: STEM education is going to be trendy especially on the African continent. We are going to need more and more scientists than ever before. And these scientists must be groomed from the right age, 3 to 4 years. And that is what we are going to do at Young Engineers. It is an idea that nobody, less than 0.1% of Ugandans has embraced. It is an idea that is going to engulf this country in the next less than 5 years from now. People have not woken up to it. Because Africa is the continent of the future of its vast mineral wealth, its beauty, vast tourism potential, vast agricultural potential, it has the potential to feed the entire world. The challenge is we lack science and technology. STEM educations solves that bottleneck. Science and Technology will lead to integration which is the other trend.

Information Technology is the second. You are looking at discoveries in IT. More IT based solutions. Tech-preneurship. If you have a simple phone like this, then you don’t need this huge land to produce something and rule the entire world. Look at Amazon, Facebook, Google.

Ian: Someone described these as the new forms of leverage. In the past you had labour, where you employed other people to do the work for you. Then the next form of leverage was money. The new form of leverage is the code, technology, the IT that with basically nothing, you rule. I was seeing something on www.aliexpress.com where you could ship something here in your name and re-sell without having a factory.

Rugyendo: Yes, that’s actually my next trend which is Globalisation. Then entertainment, sports. People are looking more on how to be happy. You have tourism of any form, of any nature, because the world is shrinking. I am also looking at food. We live to eat. Food is going to continue to trend. Why? Population is increasing, land cannot increase. Then Shelter as the land shrinks. So whoever invests in Shelter is preparing for the future.

Ian: What big ideas have you changed your mind on in the last few years? One of mine is that I tended to see change as sporadic, seismic and radical, now I am more inclined to the evolutionary path of change.

Rugyendo: One of them was multi-party democracy. When I was at campus I started a party with a friend of mine. That time we were under a one party system. The party we formed was called “Front for Multiparty Democracy” aka FMD. We made notes, wrote the preamble, what we want, what we felt. I was in second year fighting a lot for multiparty. Then we moved to multi-party, I reflected and thought; “wait, are we ready?” I was a strong believer in multi-partyism but along the way my ideas on it have changed. Because our attitude as an agrarian society we don’t seem to understand how parties work. I believe they need to evolve out of tendencies that come out of a system like this that we have had over a long time. Because when you have a long dispensation of continuity and stability, then that period of time should have helped us evolve new parties, new thinking, new ideologies. Not the ones that are based on tendencies of the past. For example now, out of NRM, I expect to get parties that are republican in nature, workers based for example, of interests, parties that are interest based. Not ethnic, or religious based. It should be parties of interest.

What is our interest? Our interest is for example Digital Technology. So you can have like a Digital Party sprouting out. Our interest is STEM education, our interest is Infrastructure, our interest is cultural preservation, environment. If you have such parties around interests, then you have people of different shapes rallying together around one interest that is of importance to society.

In the last election, one of the parties that really for me interested me was of this man, Maj. Gen. Biraro which was based on farmer’s interests. Because a farmer in Arua faces the same challenges as the one in Kisoro. And so does the one in Bududa.

Ian: What mistakes do you see most people often commit? For example, I think most people try to cash out on the short term. They are very short-term oriented.

Rugyendo: Truly. I agree, very many Ugandans are short term led. They believe in the interim. They live in the interim. They don’t have a strategic thought process to say in 10 years this is what we supposed to be doing. We need to do this in order for us to achieve that in 10 years time. As long as somebody has gotten what they want at that point in time and taken it to themselves, that’s it.

The other mistake I see is selfishness, greed. How does somebody for example preside over the importation of expired drugs, of fake drugs and feed them to the people just because you want to be rich? Because you want to buy square miles of land, put cows and that’s it. And you risk people’s lives including even your own. These are the things that really bother me quite a lot.

Ian: Do you have a typical day routine? A morning routine?

Rugyendo: When I was in the Seminary, we strictly used to wake up at 6:15am. So that has stuck in my head up to now. When it is 6:15am, I am either up or I am getting up. But normally if I have not had a night of thought processing, I wake up at 6:15am. But if I have had it normally by 4am I am up and trying to put down an idea on the phone. Sometimes my wife wonders what I am doing on the phone but I am just sending emails to myself. When an idea comes, I send it to myself. I tend to self-email all the time. I just go into my Rugyendo email, compose, send it to myself. So that when I wake up and go to my laptop, I will find something.

I wake up and of late my family and children like praying. So we pray in the morning. I was not used to that. But now it has happened in the last one year. I also wake up and do brisk-walking. I have a condition I am trying to manage and I am encouraged to exercise a lot. It is kind of heart-related. Three times a week I try to do some road running in the morning, but mainly not very aggressively. I do from the side where I stay in Kiwanga and go up to industrial area here, then go back home, do breakfast. If I don’t have an appointment in town, I come straight here to work. I believe a lot in training, constant training. Even on assignment, I train on it with people I supervise and we even rehearse what to say while in the field because I am so much into marketing. Here, we run the place by way of meetings. We are always meeting every minute. There’s always a meeting like almost every other hour. We are in meetings throughout the day. I then participate in editing some of the stories or making phone calls to land an advert or helping somebody connect to a client. That’s how my day goes.

Ian: What is the one quote that speaks to you on a deeper, more thought-provoking level?

Rugyendo: It was a quotation made during the Trial of Didan Kimathi by Francis Imbugua in the book; ‘Betrayal in the City’. When Kimathi was being tried during the Mau Mau trial, he said that “the outside of one cell may as well be the inside of another.” That quotation teaches that over time even when you think you are free, you may actually not be free. You might be the other side of the coin, the other side where it is buttered better and think you are free and then you are making life difficult for this other person who is on the other side because you are disagreeing and then all of a sudden, the tables are turned and you become the hunted. And I see this happen all the time and repeatedly in very many situations, be it in church, be it at school, even at work places.

You have somebody who is very tormenting, top manager harassing workers then all of a sudden this worker is the boss. I have seen it in the army, in security forces, somebody incarcerates another one then a reshuffle comes, the one who is in jail is appointed the boss. It teaches quite a lot. When Kimathi was in jail, he was being tormented by a white colonial officer. So Kimathi told him; “you are out there, but that outside of this cell may be the inside of another.” And it need it turned out to be. It is a quote that has stuck in my head since the time I was in Senior 4.

Ian: Probably in 100 years, 200 years, everything you’ve ever done will almost be done. How do you wanna be remembered? What kind of legacy are you here to leave? What is that memory that you want to stick in people’s lives when they think of Arinaitwe Rugyendo?

Rugyendo: I want to be remembered as a man who was good to the people on his way up because he knew he would meet them on his way down. And who inspired young entrepreneurship in Uganda. Because the time we started, the belief was that young people could not do anything. And I believe it is the very reason you are even interviewing me. Most of the interviews I have done, media, talks, are all about people wanting to hear my story as a young person when I was 20. How did I do it? So it tells me something that there was something lacking in that age group at that time when we also started. I want to be remembered as somebody who spurred that and motivated a number of young people to go and start their own things, young entrepreneurs and succeeded.

Ian: If you had this one great moment to address the whole world, all listening to you. Or if you had this gigantic billboard that the whole world could see in this moment, what are those words you could tell to the whole world?

Rugyendo: I would say; everybody, every citizen of the world should stop hatred, should stop greed, should stop being selfish, should be humble, should be considerate. And the rich nations of the world must open up their borders, their markets, for the poor nations to trade at an equal level. I would say no to nuclear weapons. We do not need them. One minute it can land in the hands of a mad man and the whole world is obliterated. I would say No to fighting, no wars. Let peace prevail, let the environment be protected, let everyone have some food and let everyone have a job in order to take some food home in the evening. At any one moment, everybody should say one little prayer at least once a year to God for the glory that we have as human beings. Because I think we are the most advantaged and luckiest among all the species of the world. So we need to thank God for that. And build a more equitable, just and orderly planet.

Ian: Thanks very much for this moment.

Rugyendo: Very welcome man. It’s been tough!