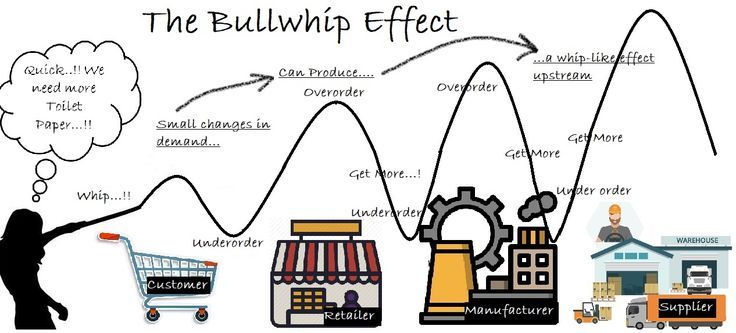

The Bullwhip effect was a ground-breaking concept in supply chain management. For the first time, the world became aware of probably the biggest and most enduring challenges in managing a functional supply chain. Stated simply, the bullwhip effect is a distortion of information in the supply chain. That a small signal at the last mile or end of process creates a large signal at the start of the process.

Let’s take an example of Mukasa ordering three bottles of Guinness on a Friday night while on a visit to his village in Nkokonjeru. The waitress at this Nkokonjeru bar will tell the manager that there’s an increased demand for Guinness in the area. Thus, if the manager was stocking half a crate of Guinness, he will now stock a full crate. The depot that supplies this bar will furthermore double its stocking, if it was stocking 30 crates of Guinness, it will now stock 5 extra crates because of this increased order from Nkokonjeru.

Similarly, the Uganda Breweries Limited (UBL) distributor in Mukono will go from stocking 500 crates of Guinness to 600 crates. UBL will now be forced to produce even more Guinness, thus put in more production runs, and brew more beer. Ultimately, UBL will also notify its suppliers for the Guinness Raw materials such as GFE to send in more quantities. Now all this distortion is coming simply because of this one night where for the first time in Nkokonjeru, someone order three bottles of Guinness.

Worse, by the time everyone along the supply chain responds to this distortion, the damage will be done. And this will be evidenced by exaggerated inventory levels, this will lock up money, furthermore, there’s a cost to keeping this inventory.

There is only one way to always beat the bullwhip effect, it’s having ‘wise’ forecasting models. I say wise because most places have data, but they can’t make sense out of it. Thus, for most people, it’s not even information, it’s just data. Just because you know that five blue dresses were sold at Woolworths yesterday is just data. This data must be processed into information. From information, it must then be translated into insight. One must understand who bought those dresses, when were they bought, why those dresses? What if information comes out that it’s men who were buying the dresses? What if these men were responding to some blue dress challenge by their girlfriends? A wise forecasting model makes sense of such spikes and seasonality. Businesses must master this process from data to information to insight and finally intervention or action.

In rural Uganda, the commodities markets affect various regions differently. Some regions follow the coffee season, others the maize season. If it’s in Mpigi, lots of demand will also be dependent on the ginger harvests and planting seasons. The models must have the ability to make sense of such regional seasonality.

Definitely, the supply chain of the future must be one that’s comfortable with randomness. The future can only get more random. And the way to deal with random futures is to be agile/flexible, adaptable/dynamic and finally to have alignment with all the multiple players in the supply chain. We should now speak of fully integrated real-time supply chain information systems. We often speak of integration, but integration must be on the information level.

Often in the supply chain, everything will be discussed from the product to the people. But the one crucial thing is often forgotten and that’s the information stream. Supply chains of the future are about information flow, and translation. Should the extra 3 bottles of Guinness really translate to an extra stock of 2 Guinness cases at the bar? Is the new demand really representative of growth in demand? How do you separate one-offs from new trends and patterns? This is where the wisdom comes in.

One of the ways of solving this is to ensure that the supply chain is speaking from the same system. Corporations such as Diageo as solving this with systems such as Diageo One, ensuring that bars are ordering through a system that gives the headquarters real-time visibility. But organizations must ask the question; ‘then what?’ What if we now know that 10 cases of Guinness were ordered in Nkokonjeru yesterday? Then what? Well, some will short-cut the thinking and simply say Guinness is growing, so let’s produce more Guinness. That’s reactionary. That’s when the sales team on the ground should seek insight. Could it be that there’s a growing myth that Guinness improves manpower? Could it be that the current recipe is fitting the palette of the consumer? Ultimately data without insight is nothing, absolutely nothing. The teams on the ground should be prompting with more ‘Whys’ to understand spikes and growth trends.

Ultimately end to end visibilities across distribution channels ought to also enable organizations to shuffle products from where they are least demanded to where they are most demanded. If a distributor of Cocacola in Masindi has an over-stock of Sprite that’s needed in Hoima, it would be better to shuffle that around to Hoima. Instead, what currently happens is that the Hoima distributor will have to await a truck from Kampala or Mbarara to fulfil this demand. Again, data visibility should enable all parts of the supply chain to sense and respond in the most optimal way.

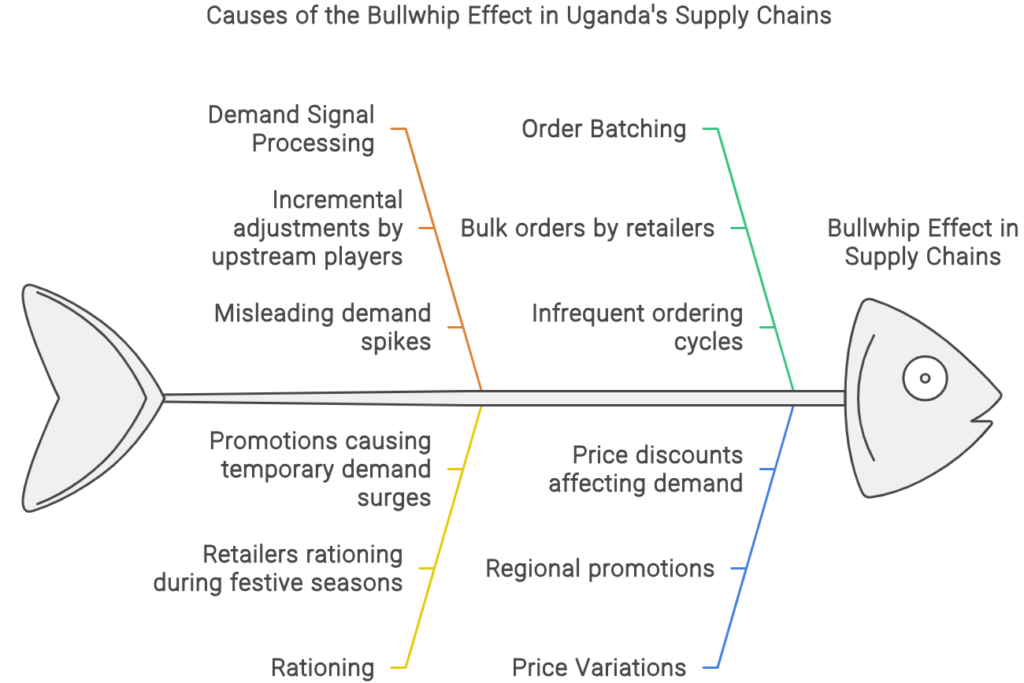

From Hau Lee’s ground-breaking paper in 1997 around information distortion in the supply chain, there were four major causes. The first source was in how the demand signal was processed with every player upstream factoring in an increment, the effect of rationing (for example retailers tend to ration during the festive seasons), order batching and price variation sources. Price Variation could come from an organization carrying out a promotion in an area or region. For example, if Mandela Millers carries out a two for one promotion for its wheat flour, that will ultimately push up demand. Thus, forecasting models should have an element that accounts for such price variations and attach an effect of the same.

We are at the beginning of the moment in Uganda when the best supply chain will win the market. Organizations in Uganda from now onwards will compete fully on their supply chains and less on their other strategies. And the only way to do this is to build agile, data-demand driven supply chains. As organizations grow bigger, the bullwhip effect even becomes larger and more catastrophic. This bullwhip effect is also common during new product introductions in the market, during product de-listings. Again, organizations must be on their toes to sense and respond and have learning forecasting models.

The lesson for supply chain managers is to recognize that orders in the supply chain do not automatically reflect actual customer/consumer demands. It is to recognize that the bullwhip is more alive today than yesterday and it grows bigger as the supply chain expands. The bullwhip effect results in purchase of excess raw materials, additional manufacturing expenses created by excess capacity, increased warehousing costs, additional transportation costs to mention but a few. Worse, for organizations with multiple products, it also means opportunity cost in terms of products that are not produced as one is blindfolded by a bullwhip effect on another product.

The Bullwhip effect is the last mile in any Supply Chain transformation endeavor. When all is said and done, when an organization has real-time visibility from the point-of-sales data, the organization will still have to deal with the Bullwhip effect. We propose in this paper that the only way to crash the bullwhip effect is with an integrated supply chain system that talks wisely with itself. It all comes down to the sense that’s made of the information flow.

From where we sit as Ortega Group, this integration of the information flow in the supply chain must also be aligned with efforts to kill data silos. Although most organizations have transitioned to digital data collection and processing, departments, functions and units continue to function with data silos. This comes down to 80% of most company data is inaccessible and locked up in a data silo. Without breaking data silos, organizations cannot generate timely insight upon which to base decision making. These data silos can only compound the bullwhip effect.